Using Simulation to Promote Equitable Care and Improve Health Outcomes

As our global population becomes increasingly more diverse, so too does the patient population. And, this should affect how healthcare professionals train for their roles.

There has been a significant focus on promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in healthcare education with the intention of acknowledging health disparities and improving the quality of care and health outcomes for groups outside of dominant power structures.

The problem is known – disparities exist across dimensions of race, ethnicity, gender, age, education level, and geographic location. The solutions can seem far less certain.

There are societal, structural, and personal biases that negatively impact health disparities globally. Where we seek to focus is on the training of healthcare professionals and how stronger training methods can develop more culturally-competent and cognizant providers.

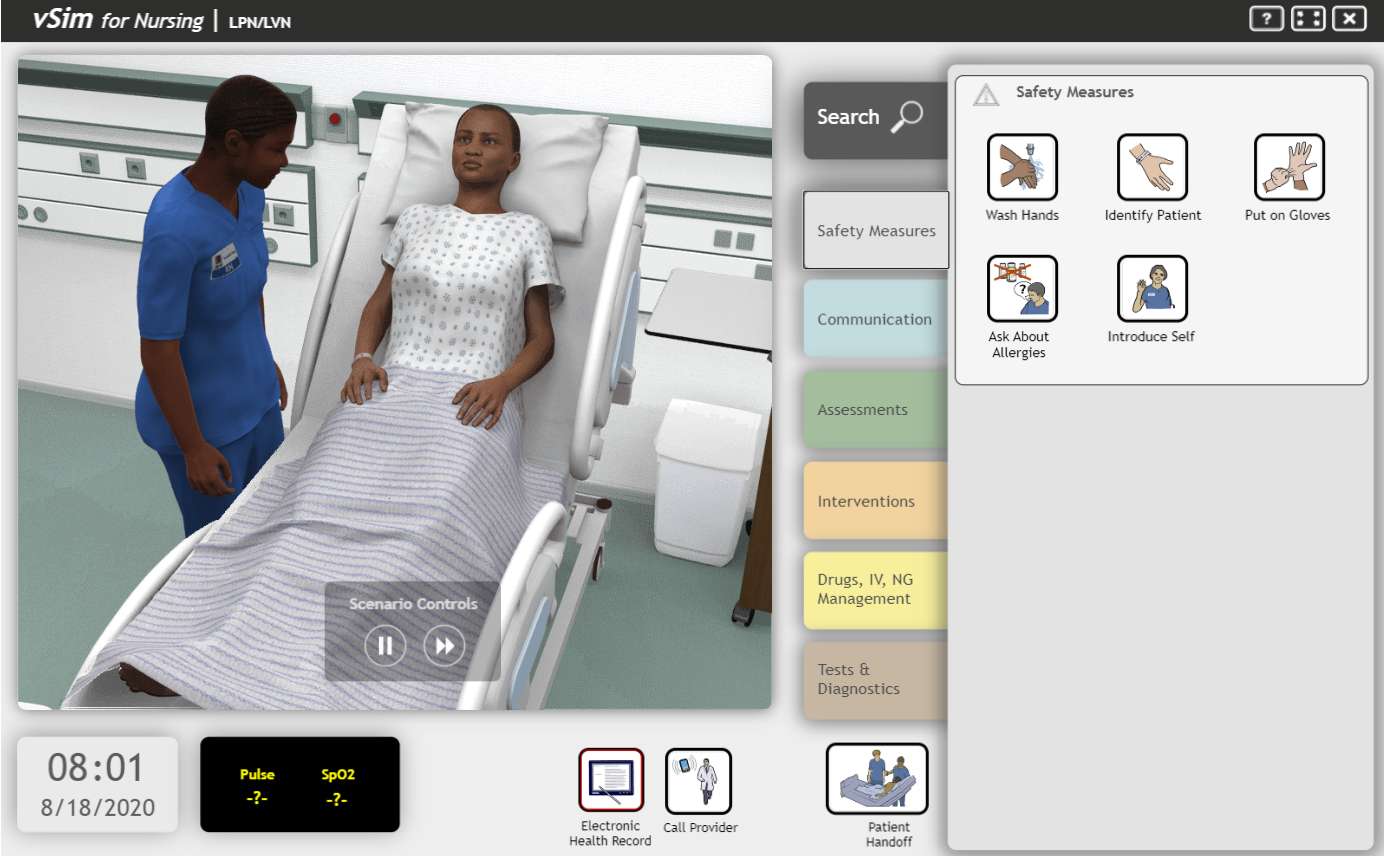

There are many benefits of using simulation to train healthcare providers and providers-in-training, including, making knowledge come alive, increasing clinical understanding, boosting confidence to treat acute cases, and many more.

In this article, we discuss how simulation can help to reduce implicit bias and mitigate risk to patients of diverse backgrounds. This article includes example scenario cases and helpful tools to make or propose an educational shift in your organization with the goal of guiding more culturally-diverse learning experiences and influence safer, more equitable healthcare.

While the term "disparities" is often used to describe differences between racial and ethnic groups, there are many other dimensions of disparity – particularly in healthcare. These dimensions, or health determinants, are complex and intersectional by nature. Therefore, they require careful consideration when preparing healthcare providers for their roles. Some examples are:

Race

Ethnicity

Age

Gender

Sexual orientation

Education

Culture

Heritage

Religion

Geography

Physical abilities

Socioeconomic status

Note: For the purposes of this article, the terms “diversity” and “cultural diversity” will encompass these many characteristics.

Looking at the overarching factors that affect a patient’s care, simulation cannot solve all concerns. However, it can help to change behavior faster and better than other methods used to train healthcare providers.

Compared with didactic teaching methods, such as lectures, discrimination training, and policy updates, simulation is best known as the method that makes learning “stick”. Hospitals and nursing schools that have adopted simulation training have seen the following improvements:1, 2, 3

First and foremost, you will have to switch the lens that both facilitators and learners are looking through. Rather than centering your simulation around specific clinical tasks or specific teamwork strategies, you want to turn all attention to the patient. Just the patient and any of the cultural characteristics that might impact their health.

This seems intuitive in healthcare. After all, the patient is the primary concern. But how often are cultural characteristics either overlooked or ignored with well-meaning intentions to treat all patients the same?

The goal of simulating for diverse patient populations is to distinguish one individual patient from the next. These differences are the key to providing safe and equitable care.

Design your simulation scenario around a patient group that is faced with negative health outcomes. Focus on areas where there is the most room for improvement. In this article, we categorize research on select at-risk populations and offer some suggestions for planning a simulated patient case.

Simulation can help providers recognize cross-cultural issues in interviewing, communicating medical information, and providing treatment for patients from varying ethnic and racial backgrounds.4

Your goal may be to teach learners to look for physiological symptoms that are unique to different skin tones. Or it may be to bring awareness to an ailment that typically targets a specific ethnic group.

To a certain degree, simulation asks that learners dispend disbelief. However, by using a simulator that represents a real person you can bring the scenario to life.

Multiple studies have shown that pain is often undertreated in Black expectant and new mothers.5 Explore that phenomenon through a simulated experience: A 34-year old Black woman returns to the hospital 3-weeks postpartum after a high-risk pregnancy battling a clotting disorder and high blood pressure. She had a C-section birth and is suffering a painful hematoma at her incision and has also been suffering headaches, blurred vision, and leg edema.

Inadequate provider-patient communication is often a contributing factor to patient noncompliance, poor patient outcomes, and litigation.6 In multicultural populations, the issue of miscommunication can become detrimental to a patient’s health and it is critical for providers to avoid making assumptions based on race or ethnicity. Simulation can introduce learners to the practice of asking for a person’s background, how they choose to be identified, and what their preferred language is.

Simulation also affords an opportunity for learners to get comfortable navigating and removing language and cultural barriers. For example, here are some steps toward reducing risk to a patient that can be incorporated into your scenarios.7

Encourage your learners to use the L.E.A.R.N. acronym:

Include the role of an interpreter.

Train learners to use closed-loop communication when speaking with the interpreter and patient. This means repeating what was said and ensuring that the patient ultimately understands what is being discussed.

In the 1990s. women’s advocates drew attention to the fact that women were largely being left out of clinical research.8 Although studies since then have included more women, there is still considered to be a "knowledge gap" surrounding women’s health. Diseases that disproportionately affect women (like autoimmune diseases, fibromyalgia, and chronic pain conditions) have largely been under-researched. This, in addition to anecdotes about providers dismissing female patient concerns, has resulted in a "trust gap" that affects women’s perception of healthcare services.9

Heart disease is a leading cause of death in women around the world.10 While male symptoms are more well-known, women can sometimes exhibit no symptoms at all. Simulate a middle-aged woman reporting pain in the jaw and throat as well as nausea. See what your students come up with.

Similarly, while most studies on gender disparities focus primarily on males and females, it is important to include transgender and intersex patients in your educational curriculum too.

Transgender people face an increased risk of HIV infection (particularly among transgender women of color) and a lower likelihood of preventative cancer screenings among transgender men.11

A simulated learning experience focused on any type of gender disparities will require realistic genitalia and anatomical landmarks, as well as strong rapport-building skills. Not feeling comfortable asking certain questions (such as sexual orientation, a patient’s preferred pronouns, or whether they are taking hormones) can create a barrier to quality care, and simulation practice can help to remove that barrier.

In addition to increasing in the sheer number of people, aging adults also experience a higher risk of chronic disease.12 Experts have raised concerns that healthcare systems will need to prepare for increased incidences of chronic conditions as well as implement multidisciplinary approaches to managing a patient’s case.13 And, as the demand for home health and personal care aides also grows, there is yet another segment to incorporate in the elderly continuum of care.14

This is precisely where simulation can make the difference. One study measured the impact of simulation training on skills required to address delirium, falls, elder abuse, and breaking bad news to patients and their families.15 Using a combination of standardized patients, simulators, and simulated clinical documentation, learners significantly improved in:

Often, SES (Socioeconomic status) is interpreted through appearances alone. One way to shine a light on the learners’ implicit biases is to run the same simulation two times – once with a low-SES homeless man and once with a high-SES businessman.

For healthcare providers to address unconscious biases, they must learn to recognize intrinsic blind spots. Many of these blind spots are the result of confirmation bias, which means reinforcing prior beliefs while disregarding new information that doesn’t reinforce those beliefs.

In order to teach the constant vigilance and self-awareness required to provide unbiased care, it can help to set expectations and ground rules before you begin your simulation.

Below, we provide a mock-up of what your guidelines might look like.

I am a willing participant of this simulation and, as such, I will be fully present, engaged, and open to new learning.

I agree to contribute positively to the learning environment and maintain an open-mind to observations, feedback, and questions.

I understand that my beliefs, values, and culture may not be the same as someone else’s.

I understand that this is an opportunity to try different ways of providing care, but that does not necessarily mean previous ways of treating patients have been “wrong.”

I understand that some aspects within this learning experience may cause me to question the world around me.

At the conclusion of the simulation, I will take part in a thoughtful reflection of this experience.

Those who teach using simulation often argue that the debriefing session following the simulation is where most of the learning occurs. It is only through the debrief that learners can fully absorb the information, discuss what they’ve learned, and then change their behavior in future situations.

Cynthia Foronda, PhD, RN, CNE, CHSE, ANEF, researched and developed the Theory of Cultural Humility, which presents the framework to address the multiple influences in a diverse scenario.

Cultural humility is defined as the recognition of diversity and power imbalances among individuals, groups, or communities, with the actions of being open, self-aware, ego-less, flexible, exuding respect and supportive interactions, focusing on both self and other to formulate a tailored response. Using this framework to navigate the simulation debrief can help learners critically reflect on past events with the lens of better recognizing and understanding diversity as well as cultural humility.16

The reflective process of debriefing is a cornerstone of Kolb’s experiential learning theory.17 By following a concrete experience (the simulation) with observation and reflection (the debrief), learners can form ideas about their performance and determine what they need to do differently next time.

Some essential elements of effective debriefing include:

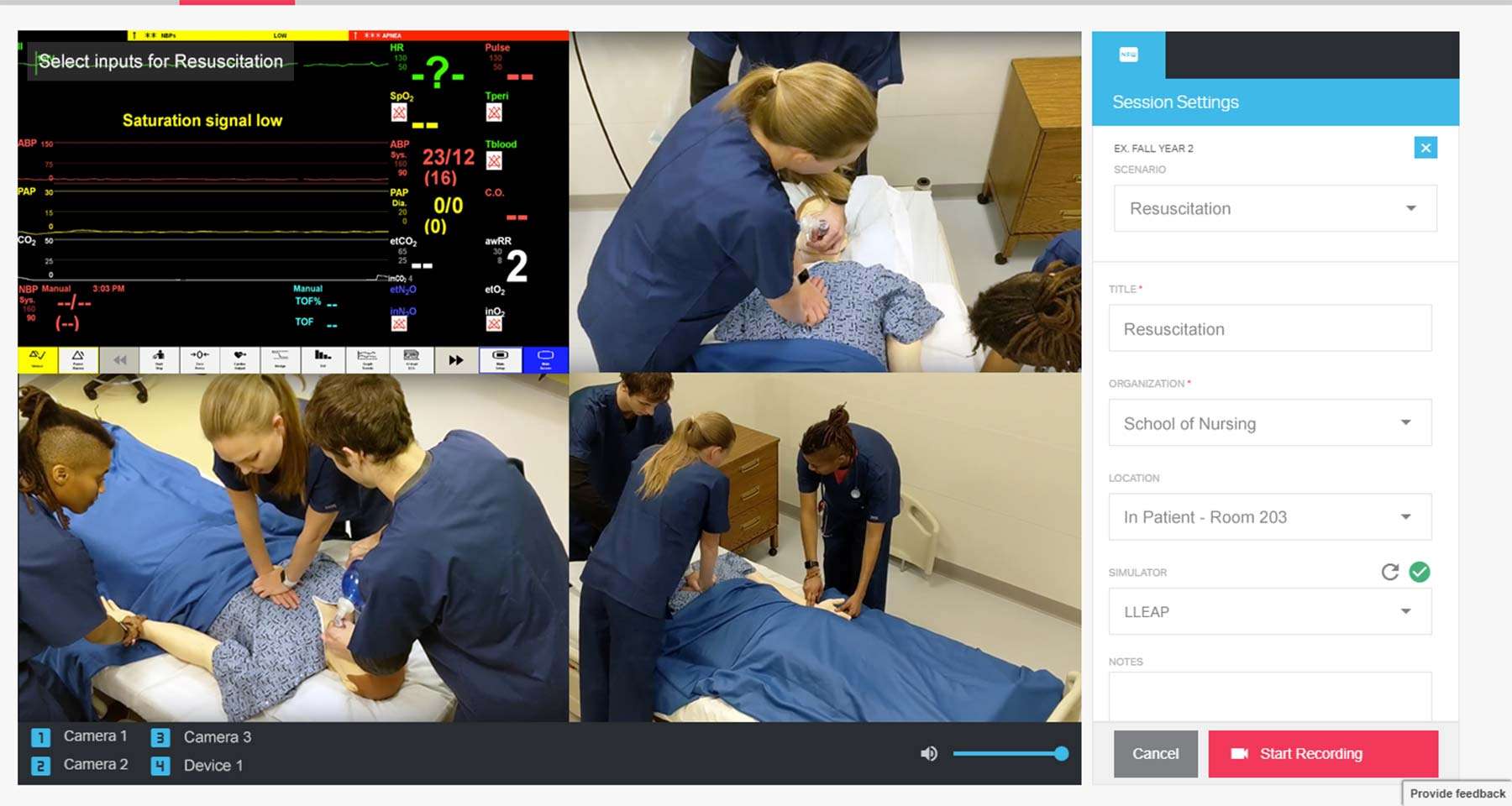

Debriefing a simulation scenario encourages better understanding of the learning concepts, but it’s worth considering how to take this one step further with video recording. The line of debriefing questions will uncover a retrospective look at the learners’ performance. Giving these same learners an opportunity to review a video playback of themselves and their peers can lead to a more thorough analysis of the situation. This includes spotting and calling out stereotypes, biases, and inequities that might otherwise go unnoticed.

SimCapture can help you to manage, assess, and debrief your simulations. It can also provide reports and statistics on performance, as well as capture student evaluations.

In healthcare, there is a known underrepresentation of cultural, gender, and ethnic diversity during training and in leadership.

To truly serve the needs of a diverse population, it is critical to implement training that will promote cultural competence, cultural humility and a strong sense of clinical empathy.

Simulation is a strong means to develop the necessary skill set to provide high-quality care for all patients. However, as we wrap-up this article, we'd like to leave you with one final thought: Implicit bias, which can stand in the way of safe patient care, cannot be eliminated overnight. Nor can it be reduced by one singular training session.

Reducing bias and providing equitable care requires a life-long commitment and unwavering vigilance.

At Laerdal, we are committed to providing you with solutions and support to help save more lives – across the entire spectrum of patients, ensuring equitable healthcare for all.